Reading time – 7 minutes

When you’ve spent nearly 25 years largely focused on efforts to prevent climate catastrophe, and a heat dome parks itself over your head generating the greatest heat wave in recorded history, it kicks you in the gut. The natural response is grief. I’m feeling it, as are many of us.

In 2000, flying back to Seattle from doing a climate presentation in Europe, the flight path took us over Greenland. It was a sunny August day. Over the glaciated island’s west coast, I could see fleets of icebergs sailing into Baffin Bay. They likely came from Jakobshavn, one of Greenland’s major glaciers, probable source of the iceberg that sank the Titanic. That their crystalline shapes were visible from 36,000 feet up indicated just how massive they were.

By coincidence, I had just been reading about how Greenland ice melt could interfere with the Gulf Stream, causing major climate disruption. I had already been grappling with climate full-time for several years, writing about the significant climate impacts happening even then. Looking out the window at those icebergs, it struck me we were not going to prevent climate extremes. The combined inertia of the climate and political-economic systems stubbornly resistant to change ensured that. We just needed to do everything we could to limit the impacts and slow the changes, so Planet Titanic would not go down and future generations could have a chance.

Those extremes have arrived. What was predicted is coming about. Atlantic currents are the weakest in at least 1,000 years. The Amazon rainforest has turned from a carbon soaker to a carbon source. Heat waves, droughts and wildfires have been hitting the North American west and Siberia recently. Storms and floods are inundating Germany and Belgium far beyond climate change predictions, and soaking India as well. New reports of climate extremes seem to come in weekly.

Even with all that, there’s something about climate extremes coming home to where you live that pierces through to an emotional level in a way that reading or watching a video doesn’t. Communicating in a visceral way what climate extremes really mean. Certainly, when in summer 2020 wildfire smoke gave Seattle the second worst urban air in the world and Portland the worst, it really began to hit home.

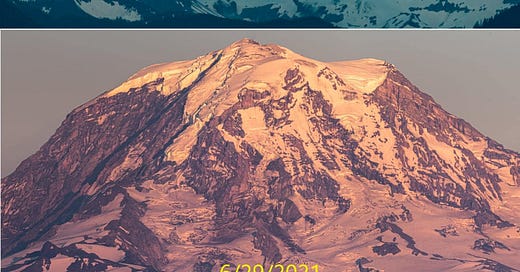

But this June’s heatwave across Cascadia pushed it to a new level. We knew wildfires were coming. 2020 was predictable. But we didn’t know this intensity of heating we have seen in 2021 was coming so soon. We’ve been underestimating the momentum of climate disruption. In Seattle, where only three days shot over 100 degrees in previous history, three consecutive days reached above that mark, topping out at 108. Portland averaged 112 degrees over those three days, six degrees over any previous average, with a peak of 116. The largely native community of Lytton, BC exceeded records for all of Canada for three days, heating on the third to 121 degrees, which fed a fire that burned most of the town. Glaciers, which feed regional rivers, melted at the fastest rate in a century. Satellite images reveal the shocking extent of snowpack loss on Mt. Tahoma/Rainier.

Scientific attribution studies, which compare events in our world to their likelihood in a world where humanity had not added heat-trapping gases to the atmosphere, tell us those gases made the heatwave 150 times more likely. It was a one-in-50,000-year event. Crucially, and this is the kicker, even with carbon levels in the atmosphere, such a heatwave would be likely only once in 1,000 years. That does not say it will be 1,000 years before it happens next. It says that projections are not taking all factors into account, such as the way Arctic ice melt seems to be twisting the jet stream and holding heat domes in place. Climate scientist Michael Mann explains it here. The floods in Europe and intense rains in the eastern U.S. are also tied to the twisted jet stream. Droughty heatwaves and drenching inundations are two sides of the same coin.

We don’t know the full extent of what we face. We just know that with all we are seeing at a global heating of 1°C/1.8°F, while humanity continues to burn fossil fuels and dump carbon into the atmosphere at record rates, it’s going to get worse. Probably a lot worse. I know we still have time to leave our children a world with which they can cope, when climate disruption is not causing civilization-collapsing chaos. I believe we will. But the bar is being raised higher, and uncertainties are growing.

If there is any virtue in the situation, it is clarity. There is no evading or soft-pedaling the clear and present danger confronting us. It is staring us hard in the face. We as humans are hard-wired to respond to visible threats, ones that punch us in the gut, hit us at an emotional level. Here we are.

And with the rising crescendo of climate chaos, the crisis is in the forefront to an unprecedented degree. Public concern is increasing. The media is starting to make the connections to catastrophes breaking out around the world, though much more consistent connecting is required. The European Union has adopted a transformative plan to reduce climate pollution 55% by 2030. But whether it can overcome hurdles among 27 member states, or cut pollution enough to stay in climate boundaries, remains a question.

In the U.S., blockages in Congress have pushed key climate measures out of the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill proposed by the Biden Administration. Activists and Democratic electeds are pushing back, saying No Climate No Deal. A $3.5 billion budget reconciliation bill does include vital provisions including supports for solar, wind and vehicle electrification, and a clean electricity mandate. But narrow majorities and the power of coal state Senator Joe Manchin leave things up in the air.

That gets to the key issue – political power. There is much that individuals can do to reduce their own carbon pollution, and that should not be overlooked. But we are locked into systems that limit what individuals can do on their own, such as car-centric transportation networks that force many of us to drive whether we like it or not. We need fundamental systems changes starting this decade that dramatically cut energy use while replacing fossil energy with solar and wind alternatives. That is a matter of public policy, which entails breaking the lock powerful economic forces have on the political system.

The only way to do that is mass people power, getting in the streets and halls of government to pressure political leaders. To speak in a very loud, collective voice to tell the politicians lip service is not good enough, and business as usual will not cut it. That we will not accept leaving our children’s world a complete wreckage. Action is the answer to climate grief. Join with a climate group that focuses on people power mobilization, such as Sunrise Movement or 350.org. Many local areas have affiliates where you can personally connect with others who share your concerns. (I can’t find a good tool linking affiliates, but if you ping me in the comments I’ll do my best to hook you up.) Emily Atkin also provides a number of action options in her HEATED newsletter.

We face tremendous uncertainties, with many rational reasons for discouragement. I struggle against this, as I am sure many of you too. What helps me is to apply a lesson from Buddhist psychology. When overwhelmed by one factor, balance it with the opposite. The word for the opposite is contained within the challenge. Meet discouragement with courage. Facing what we face, we will need a lot of that in coming times.

Please subscribe to The Raven or sign up for the free email list here. Your subscription will support my work and help keep access to The Raven free for everyone.