7 minute read

A salmon return ceremony

It may be the most profound four words I heard in my life. Strange to my ears when I first heard them, but deeply meaningful as I pondered them over the years.

The occasion was a spring salmon return ceremony at Cook’s Landing, the longhouse where David Sohappy and his family lived on the north side of the Columbia River near Hood River, Oregon. It was 1986. David was an already famed defender of native treaty fishing rights. He had been arrested asserting his rights, and was party to a 1969 lawsuit against the Oregon Fish Commission, Sohappy v. Smith, which drew a landmark ruling that native people had a right to a fair share of fish. It was the predecessor to the monumental 1974 Boldt decision which gave Northwest natives a right to half the regional catch.

David’s role in gaining those rights aroused vicious enmity against him by commercial and sport fishing interests, as well as state and federal fishing regulation agencies who felt their turf had been violated. There was a bullseye on him. Under a federal sting operation he was charged with illegally selling salmon. David, his son and several others close to him were facing federal prison terms in the so-called salmon scam case. Convicted in 1983, their case was on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. More on that in a bit.

I had been invited to the salmon return by Paul Roland, a friend and fellow writer at the Portland Alliance, a progressive newspaper that covered the range of issues then rising, the struggle to save old growth, the effort to stop Hanford on the Columbia from becoming the permanent high-level nuclear waste dump – later successful, and native rights struggles, among others. Paul had been writing about the Sohappy case.

The four words: “We are the salmon”

We pulled across the railroad tracks that divide the longhouse from Washington Highway 14 and entered the structure. Instantly the smell of salmon washed over us. Salmon cooking. Salmon hung and drying. The longhouse was divided into different family areas, with a large gathering room on the east end. That was where the ceremony was to take place.

As it started, a line of men stood at the end of the room facing east, drumming and singing. It was a sunny day. Through large windows looking out on the river, I could see strong winds whipping up whitecapped waves, seemingly in unison with the powerful drumming. As the ceremony progressed, the women would bring out salmon dishes and other native foods.

It has been a long time, and much of what I remember is in those few images. But the part that stuck out, which seemed so odd to my white western civilized ears, were those four words spoken by David as part of the ceremony. “We are the salmon.” I was expecting a salmon return ceremony to be something like our Thanksgiving, thanking the salmon for returning and bringing their bounties. The ceremony certainly evoked those feelings, but in David’s words were something more, an expression of the unity of salmon and people in a great circle of life that has continued from time immemorial. When you hear Northwest indigenous call themselves salmon people, they mean it.

The Seven Drums of Smoholla

David was a leader in the Seven Drums or Washat religion, taught to him as a child. He was a direct descendant of the founder of that religion, Smoholla, who was part of the late 1800s revival of native traditions that also included the ghost dancers who were shot down in the Wounded Knee massacre.

“Smoholla foretold the arrival of white colonizers who would destroy the traditional ways of the Indian tribes,” writes Paul Lindholdt. “Smoholla challenged regulations that forced Native peoples to abandon the hunting and gathering that were so integral to their traditional way of life, especially those laws that required them to take up agriculture on government-designated reservations . . . Smoholla taught his people that the way to protect themselves from the oppression that accompanied colonization was to follow their traditions and stand up for their way of life. That was one of the key objectives of Sohappy and the others in the Sohappy v. Smith lawsuit.”

In those four words, “We are the salmon,” David was expressing that tradition, born of long native experience on the Columbia, the Big River or Nch'i-Wàna in the Sahaptin language with which David grew up. It had lasted at least 11,000 years, the time of documented settlement at Celilo Falls just a few miles up the river. It probably has even earlier origins, with increasing evidence that native people were in the Northwest during the period around 15,000 to 12,000 years ago when, at the end of the last ice age, great floods washed down the river every 50 years or so. Immense waves were released when ice dams bottling up glacial Lake Missoula in the northern Rockies shattered after they rose too high.

Celilo Falls was drowned in 1957 as the river backed up behind the newly constructed dam at The Dalles. Using the river for power and navigation was more important to white civilization than preserving salmon runs and native cultures. That Celilo Falls was the oldest continuing settlement in North America meant nothing to the utilitarian culture of exploitation and gain. After all, hydroelectricity and barges produce money, while native people represent an irritating reminder of another way of life.

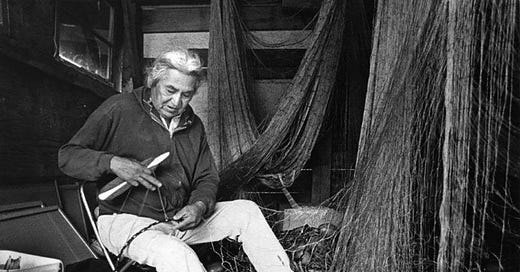

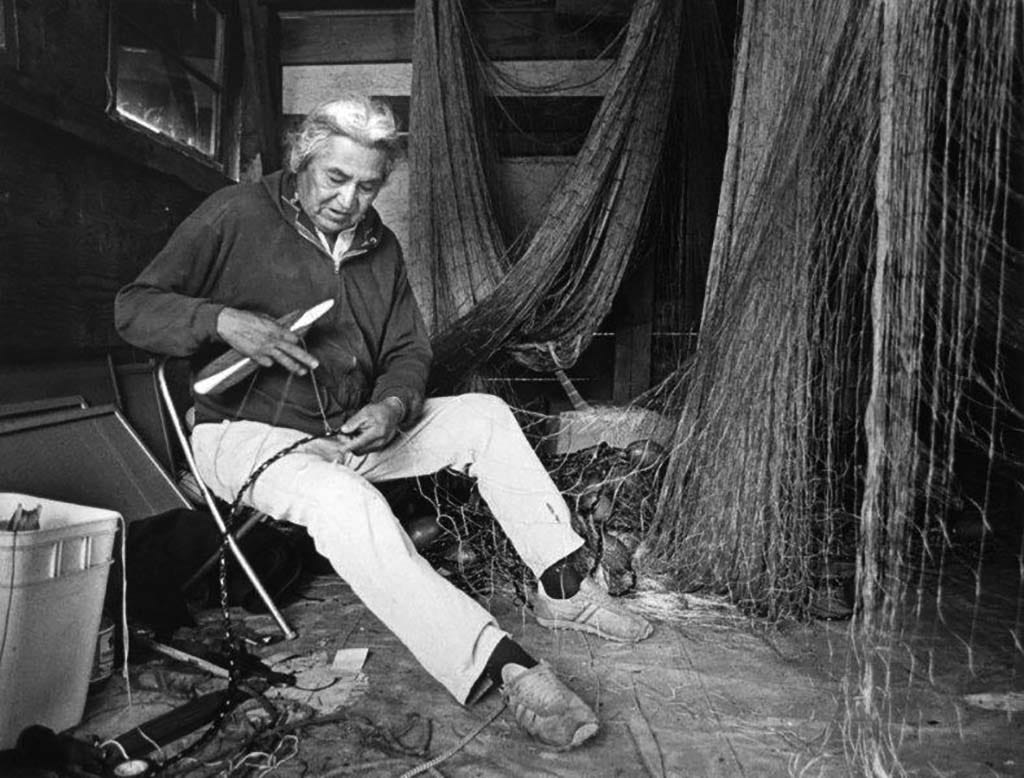

Fighting for fishing rights

Celilo Village is still there, and native people still fish for salmon and preserve their ancient traditions. Though guaranteed the right to fish “at all usual and accustomed places“ in 1855 treaties, state fishing regulators long struggled against them. They would commonly steal native fishing nets. This is what caused David to stand up and become one of the native leaders in the fish wars. He is to the Columbia River what Billy Frank is to the Salish Sea. It is generally believed this is why he was targeted.

A sting operation by the National Marine Fisheries Service in 1981 set up a fish buying stand at Celilo Village. This would cause native fishermen from the Washington side to cross over to Oregon, violating a newly passed federal amendment that made this interstate commerce a federal felony. Tom Keefe, the attorney who represented Sohappy in a companion Yakama Tribal Court case, asserts it “was written in anticipation of the sting.” (The Indian Country Today link is a good, recent telling of the story for those who want a longer account.) The amendment was supported by U.S. Senator Slade Gorton, who earlier as Washington State attorney general had been a nemesis of native fishing rights.

Sohappy and his fellows were caught in the sting and arrested in 1982, even though the sting had taken place before the law was signed into effect. Prosecutors charged them with an extensive operation responsible for 40,000 fish missing on the river. In the end, it was found the fish had merely migrated to a side stream because they could not pass through an illegal discharge of fluoride from an aluminum plant. David was actually charged with selling 317 fish, and his son 28. Both were convicted in 1983 and sentenced to 5 years. Three others received lesser sentences.

In 1986, when the salmon return ceremony took place, they were awaiting word on whether the Supreme Court would take up their appeal. It did not. In the companion case in Yakama Tribal Court, the five convicted in federal court were found not guilty in 1987.

But that didn’t matter to the feds. David and his compatriots were forced to report to federal prison, where they would serve terms mostly thousands of miles away from their families. After a healthy diet of salmon and a life in the outdoors, prison wrecked David’s health, leaving him impaired with a stroke. U.S. Senator Daniel Inouye, who chaired the Senate Special Committee on Indian Affairs, took up David’s cause, and asserted the sentences did not fit the crime. He and his son were released in 1988 after 20 months. He would die three years later at 65.

Who are we?

The absurdity of blaming native people for declining salmon runs when the fish have to fight dams, road culverts, deforestation, polluted runoff and commercial fisheries was always clear to the defenders of David Sohappy and his companions. It is the predominant civilization that is responsible for shredding the great circle of life David called out when he said, “We are the salmon.” Replacing an enduring culture that existed in balance with its lifeplace for millennia with one that reputable analysts consider at high odds to collapse in decades.

In my later musings on David’s words, I wondered what we could say that would represent the equivalent. We are the oil, the gas, the coal, the uranium? We are the soil being eroded to grow our food? What enduring sustenance can we call out, when our civilization is exhausting the very roots of sustenance?

In our civilized world we are separated from those roots by myriads of abstraction, having nothing like the sense of connection possessed by an indigenous culture that has lasted for thousands of years, and still persists. That separation is why those four words seemed so strange to me on first hearing. The way they bring that separation to the foreground is what has made them such a profound memory over the lifetime since. I am not sure how we get back to such a connection, as far as we are from it in our modern world. But I know long-term human existence on this planet depends on us finding ways to rejoin the circle of life. We can learn from the people who were here before.

Other good links to dig in further are this 30-year retrospective from the Yakima Herald, this 50-year perspective from Cascadia Magazine, and this pictorial essay from the Seattle Times.

Please sign up to receive posts from The Raven in your email box for free every Friday, using the subscribe button below. And if you are so moved, please subscribe to support my work.

Excellent article. Small clarification: David was represented in federal court in LA by Federal Public Defender Tom Hillier, where he was convicted of selling 317 salmon and found not guilty of leading the massive “Salmonscam” that implicated dozens of tribal fishers, over three seasons in 1981 and 1982. I represented him in the Yakama Tribal Court retrial dubbed “Tradition on Trial” that was the longest criminal trial in court history in which the true jury of his peers found him not guilty based on entrapment with a special finding that the regulations sought to be imposed on him had interfered with the free exercise of his traditional religion. Somewhere, Smohalla was smiling!

I really liked your juxtraposition of 'we are the salmon people' against 'we are the coal people' etc etc. It shows which way of life is connected to life on earth.