Secession from the left

The little known history of Northern secessionism

15 minute read

When abolitionists pushed Northern secession

A hard right government in firm control of the country, built on an alignment between the nation’s richest people and ideological reactionaries. Enforcing policies repugnant to many, stirring a movement in northern and western states for secession from the U.S. gaining widespread traction.

A picture of the future when the Republican right has secured control of all three branches of the federal government, and is pushing its agenda across red and blue states alike? No. It is a little known history that unfolded in the years leading up to the Civil War, though with relevance to that future scenario.

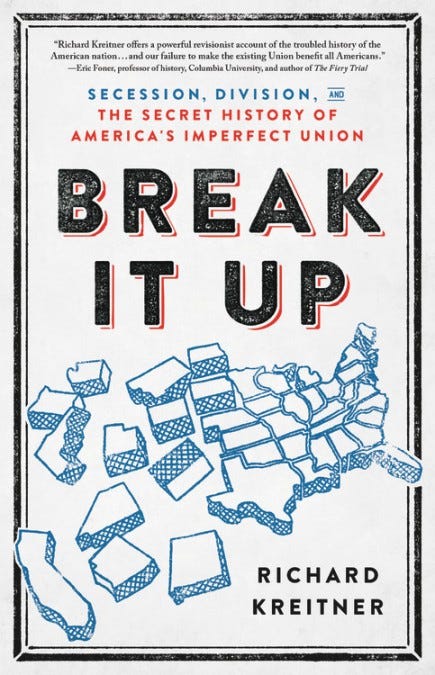

Richard Kreitner tells the story in his book, Break It Up: Secession, Division and the Secret History of America’s Imperfect Union. Told from a progressive angle by a contributing writer to The Nation, this recent work details the many breakaway movements in U.S. history, from even before the Revolution and down to the present day. This is not a full review, but a focus on the drive for Northern secession led by slavery opponents over the first half of the 19th century. (I hope to cover more from this important book in future posts.)

Secession today and tomorrow

Today, secession is primarily a movement from the right. In March, a constitutional amendment introduced by libertarians that would have created an independent nation of New Hampshire was voted down 323-13. Last November, asked about a proposed state referendum on Texas secession, Sen. Ted Cruz said his home state should secede if Democrats “fundamentally destroy the country” through such actions as Supreme Court packing and D.C statehood.

A exception that may more point to tomorrow is the Calexit movement. California secession support leapt from 20% in 2014 to 32% in 2017 when Donald Trump moved into the White House. Large Republican victories could give Republicans control of Congress in 2022 and the White House in 2024. That would subdue secession sentiments from the right. After all, why secede from a country you control? But it would stir those same sentiments from the left. A University of Virginia poll reported last September found support among Democratic voters for creating independent nations at 47% on the West Coast and 39% in the Northeast.

Of course, any serious movement for secession seems unlikely. But this week’s leak of a Supreme Court ruling that would strike down Roe v. Wade, removing federal protections for abortion rights, is roiling the waters. If that is indeed the ruling, abortion would be banned right away in 23 states. Eighteen mostly blue-leaning states would still guarantee those rights under their own laws, all but five on the West Coast and in the Northeast. The draft ruling by Justice Samuel Alito indicates other rights previously upheld by the court could be in jeopardy, including gay marriage, contraception availability, even interracial marriage.

Rightists claim they want to send such matters back to the states. But what if the theocratic elements rising in the Republican Party push it further, and attempt to create a Handmaid’s Tale regime throughout the U.S., meanwhile attacking progressive state policies such as those to limit climate pollution and gun ownership? The level of fanaticism among the hard right cannot be underestimated. Christian dominionists, a major element of the right, believe they have a moral imperative to create “one nation under God,” according to their own definition of God and his (definitely his) will. Which includes the right to carry automatic weapons into the Walmart.

Meanwhile, fossil fuel interests would like to preempt state climate policies that reduce burning coal, oil and gas, and would readily seize their opportunity. A preview came with the Trump Administration’s roll back of California’s power to set its own clean air standards, the basis on which states around the U.S. have set CO2 vehicle standards. The Biden Administration is working to restore that power, but a Republican victory in 2024 would likely once again withdraw it.

Slaveocracy in the saddle

That sets up a scenario in which a radical rightist federal government enforces a set of policies morally unbearable to people in many states, turning secession from a fringe idea into a major movement. The scenario has a precedent in those years leading up to the Civil War. For perspective, understand that in those years the South basically ran the country with help from Northern allies who also benefitted from slavery.

The cotton crop was the nation’s major way of earning wealth in the world, its leading export, and the sun around which the U.S. economy revolved. Cotton was the fuel of the industrial revolution breaking out in Britain. By far, most of the cotton was harvested by whipped Black backs in the U.S. South, home to many of the nation’s richest people. Northeast financial interests were deeply involved, bundling slave mortgages like they later bundled subprime home mortgages, selling them across the U.S. and Europe to finance plantation development. Northeast manufacturers gained major markets selling tools and clothing for use by the slaves. Midwest farmers sent pigs and corn to the South, where land was taken up growing cotton. Slavery was the basis for much of the economic growth in the early U.S. The story is magnificently told in Edward Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. (As someone who has read hundreds of books on U.S. history over my life, I would place this one in the top 10.)

That economic power translated into political power. Ten of the 15 presidents before Lincoln were slaveowners. The Constitutional measure allowing slaves to be counted as three-fifths of a human being gave the South disproportionate weight in the House of Representatives. Even as Northern populations grew, the South kept power over Congress by long efforts to balance the number of slave and free states, ensuring equal representation in the Senate. The South was united behind slavery, while the North was divided by economic interests. Put together, that provided a slaveowner-friendly majority on the Supreme Court, with disastrous consequences that proximated the Civil War.

The slaveocracy’s power was built into the structure of U.S. government created by the Constitution, including that three-fifths rule, apportioning two senators to states regardless of population, election of the president by the electoral college, and lifetime appointment of Supreme Court judges. Slaveowners and their allies, well represented at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, quite deliberately designed it that way. Southern states would not ratify a Constitution that did not protect slavery. (In The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America, Gerald Horne argues that protection of slavery from rising abolitionist forces in Britain was also a key driver in the breakaway from the crown. But that’s for another post.)

The Northern secession movement

Kreitner recounts how the first attempt to stage a Northern secession followed Thomas Jefferson’s 1803 Louisiana Purchase, which many in New England saw as spreading slavery and diluting Northern power. Timothy Pickering, a Massachusetts native who had served in cabinets under both Washington and Adams, called for “a new confederacy exempt from the corrupt and corrupting influences and oppression . . . of the South.”

A Northern confederacy would require New York’s participation, so secessionists engaged Aaron Burr, Jefferson’s vice president. Knowing he would not be part of the 1804 ticket, Burr planned a run for New York governor. Plotters saw his election as a trigger for secession. “When one plotter, Willian Plumer, predicted the Union ‘would form two distinct & separate governments,’ Burr agreed, saying not only that ‘such an event would take place – but that it was necessary that it should.’”

Secessionists planned a Boston convention for 1804. Alexander Hamilton agreed to attend. While he as a Federalist despised Jefferson, there is evidence he did not support secession. But he also was a rival of Burr, and wanted to stop his rise. So in Federalist Party circles, he denounced Burr as “a dangerous man, and one who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government.” Burr lost the party’s nomination for governor, and so challenged Hamilton to the duel in which the latter was killed. That ended plans for the convention, and sidelined the movement for the moment. Federalist moves toward a New England secession in response to the War of 1812 finally killed the party.

Several decades later in 1832, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison denounced the Constitution as “an unholy alliance” with slavery. The document bound the federal government to put down slave rebellions. “To Garrison, Northerners who revered the Constitution were guilty of perpetuating slavery . . . Only by advocating immediate emancipation could Northern whites redeem the Union and themselves. ‘It is said if you agitate this question, you will divide the Union,’ Garrison noted . . . ‘Let the pillars thereof fall – let the superstructure crumble into dust – if it must be upheld by robbery and oppression.’”

One decade after that, former President John Quincy Adams, now a congressman, rocked the House of Representatives when he introduced a petition signed by citizens of Haverhill in his state of Massachusetts calling for dissolution of the Union. Organized by abolitionists, it was another effort to get away from the slave South. Announcing it, Adams was immediately denounced as a traitor, and a censure motion was introduced. But next day, Adams defended himself with the opening of the Declaration of Independence, “When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another . . . “ The censure motion was withdrawn, and the petition spurred further discussion around the nation.

One who was inspired was Garrison. He saw in national division the creation of a refuge for fleeing slaves in the North, ending the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause allowing owners to recapture runaways. That would bleed the South and force abolition. “Breaking up the Union could be a practical strategy for ending – instead of merely protesting – the barbaric institution. ‘Nothing can prevent the dissolution of the American Union . . . but the abolition of slavery.’”

The annexation of Texas to become another slave state, and the Mexican War which followed in 1848 extending potential slave territory to the Pacific, heated up Northern secession sentiments even further. Garrison presented petitions signed by 2,834 people from 43 towns to the Massachusetts Legislature calling for the state to secede. Henry David Thoreau recognized the effort in his work on civil disobedience defending his own tax resistance. “Some are petitioning the state to dissolve the Union . . . Why do they not dissolve it themselves – the union between themselves and the state – and refuse to pay their quota into the treasury?”

Heating up in the 1850s

Matters came to a head in the final decade before the war. Kreitner writes, “the coming of the Civil War can be told as the story of a Northern (author’s emphasis) resistance movement, of Northern citizens . . . questioning whether the Union was still worth preserving at any price the South chose to name. In the free states, a new generation, sensing the future slipping from their grasp, pushed for a thorough overhaul – a political revolution.”

They had reasons to feel that slippage. The South seemed to hold the whip hand. In 1850 Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which made it virtually impossible for free Blacks to defend themselves against cases of mistaken identity or fraud. “Most galling to Northerners, the law held every American responsible for assisting in the capture of runaways – anyone who refused faced jail time.” Northern legislatures quickly passed laws nullifying the act, while Northern juries refused to convict violators.

The next blow came in 1854, when Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas led passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. It was a giveaway to the South to smooth the way for railroad construction west from Illinois. Southerners had favored a route through the Southwest. Douglas conceived the South could be bought off by allowing citizens to choose whether they should enter the Union as free or slave states. That repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1850, which allowed it to be admitted as a slave state, but limited the future western spread of slavery to a latitude extending from the state’s southern border. Out of that came Bloody Kansas, precursor to the Civil War which saw hundreds killed. It also spurred creation of a Republican Party determined to allow no further slave states, the ultimate reason why Lincoln’s 1860 victory led to the South’s secession.

Garrison, appeared at an abolitionist rally near Boston on July 4, 1854. “It was the abolitionists’ duty, he said, to “be men first and Americans only at a late and convenient hour.” He then burned a copy of the Constitution. ‘So perish all compromises with tyranny!’ Garrison declared. The crowd roared its approval and broke out in a hymn.”

In 1856 a Southern congressman pummeled Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner on the floor of Congress after Sumner denounced slaveowners for raping female slaves, severely injuring the senator. In response, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in his journal, “Suppose we raise soldiers in Massachusetts . . . suppose we propose a Northern Union?” “At one protest meeting, Emerson said he was ‘glad to see that the terror at disunion and anarchy is disappearing.’”

The election of President James Buchanan in 1856 sparked comment in Garrison’s publication, The Liberator, probably written by him. It meant “four more years of pro-slavery government.” It was “hopeless to unite under one government two antagonistic systems of society (and) “the duty of intelligent and conscientious men . . . to consider the practicability, probability, and expediency of a Separation between the Free and Slave states.”

Garrison and other abolitionists joined in an 1857 convention in Worcester, Massachusetts to promote dissolving the Union. It was organized by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a preacher who had smuggled arms to free-staters in Bloody Kansas, and hoped the conflict would “result in the disruption of the Union, for I am sure the disease is too deep for cure without amputation.” The convention endorsed the concept.

Disunion was also picking up support beyond New England. In Michigan, the Friends of Human Progress called for a “FREE NORTHERN CONFEDERACY, whose atmosphere should never be polluted by the breath of a slaveholder . . . In Ohio, disunionists petitioned the legislature to secede. A ‘national disunion convention,’ scheduled for Cleveland that fall, was called off only after a financial panic threw the country into depression.”

The Supreme Court puts the final nail in the coffin

Dred Scott was a Black slave taken by his owner to Wisconsin when it was still a territory. Because it was now a free state, Scott sued for his freedom. Shortly after the Worcester convention, the Supreme Court handed down its ruling. He could not sue because he was not a citizen, and neither were free Blacks. Even if he was, “any law banning slavery in a territory was unconstitutional. The once-extreme Southern position was now the law of the land.”

States passed laws to nullify the decision, while Lincoln denounced it as “the latest stage in the Slave Power’s long-planned coup, a conspiracy to turn the government over to ‘a pampered and powerful oligarchy of some 350,000 slaveholders.’”

“Most alarming,” Kreitner writes, “the decision threatened to erase the border between North and South. If the Constitution guaranteed slave owners the right to take their ‘property into any territory, why didn’t that apply to the states as well? Another decision like Dred Scott, Lincoln argued, would repeal emancipation in the North and make slavery national . . . That prospect infuriated the Northern Public.” The fury was to propel the election of Lincoln three years later, leading to the South’s secession and the Civil War’s outbreak in 1861.

Secession today?

Today a radical Supreme Court adheres to the “original intent” of the Constitution’s drafters, when that intent was so clearly anti-democratic and white supremacist. It is undermining rights people have come to expect and which have overwhelming majority support in decisions gutting Black voting rights and women’s rights. In repealing campaign finance regulations, the Court has upheld another aspect of the framer’s original intent, oligarchic rule by the propertied classes.

On top of that, legislatures in many states are ensuring one-party rule with radical voting restrictions and gerrymandering, while the structure of the Senate, with even representation of states and the filibuster, blocks progressive reforms also supported by overwhelming majorities. All too real is the frightful prospect for a Senate in which the Democrats are reduced to a minority that denies them the filibuster, along with the return of Donald Trump or election of a Trump-like figure in 2024. If anything is clear about the Republicans, it is that they will use every opportunity to take and keep power, and run the board for their agenda. Supported by a Supreme Court on which they hold an unassailable majority.

This is a situation in which checks and balances no longer work, and one likely to exist by 2025. Much like the 1850s, when the slaveocracy solidified its grip with the Fugitive Slave Act, Kansas Nebraska-Act, and Dred Scott decision, the radical right is likely to pass the most radical policies it can, gutting regulation of business and social services, while further rolling back civil rights. Demographics are not running their way, with a young population turning to the left, and a general population becoming more diverse. So they can be expected to take every opportunity to enact their agenda while they can, and undermine democratic possibilities to reverse it. All this in a nation becoming ever more deeply divided, with high odds that the fault lines will open up even further in coming years

Will a radical right totally empowered by control of all three branches of the federal government push its agenda to the point that it becomes morally and politically intolerable for many states and populations? When it seems better to have a parting of ways than to stick together? What seems a marginal idea today could become a movement supported by millions. Polls show substantial numbers favoring that outcome already. Kreitner’s recounting of the history of Northern separatism demonstrates that secession can come as easily from the left as the right, especially when no better course seems available. To note the potential is not to advocate for it, but instead to illustrate that the probabilities could be higher than is now commonly conceived. There may come a point when we do, indeed, break it up.

Please sign up for my free email list using the subscribe button, and subscribe if you can. I need the support.